11. Compositional Templates

There are many ways to plan a composition. One method, popular with beginners, and commonly advocated on the internet, is to use a compositional template, or pattern:

It's a simpler process. Instead of reinventing the wheel, you pick from a series of pre-planned templates, selecting the one you like best, and you change your vision to fit within it. Templates first gained popularity when artist Edgar Payne wrote Composition of Outdoor Painting, in 1941.

Most of these ideas are geared toward landscape (and seascape) painting, but you can extend it to still lifes, figurative, and even abstract works - anything really.

Are templates the right way to go?

In my own art, I avoid using templates, for several reasons. Having spoken with other artists, I haven't seen much value put into them. Many are quick to point out, using a compositional template is no guarantee of success. In fact, some of these patterns are seen as tired clichés, to be avoided - Stapleton Kearns particularly hates what he calls, "the big L."

He included it in his "encyclopedia of dumb designs". Relying on them feels intellectually lazy.

Many are based on letters of the alphabet, as if the purpose of composition were to hide letters in your art work. It's absurd, and it can lead students into thinking the letter must be visible. It needn't - most of these compositional lines should be expressed through (invisible) gestural lines:

Do you see how the above composition is circular? Note, it doesn't have to be a perfect circle to be circular. The center of the image isn't the center of interest, but rather the two figures to either side. Your eyes go first to their faces, because faces tell the story - and, in this piece, they also have very high contrast. Note the colorful shoes with high contrast that give you a reason to look down from left to right. Note the upside down, triangular pattern created by the lines of their dresses - the girl's gaze cuts straight across the top of this triangle, and if the pianist were looking back at her, it'd make the whole composition triangular. But the pianist is playing, ignoring the girl and breaking that shape. Note the objects above the piano that give you a reason to lift your eyes as they travel from the pianist, back to the girl on the left. Also, note the corner of the room that creates a vertical line above the pianist's head - giving this artwork a bit of a "cross" composition as well. Vertical lines coming out of heads like that is often considered a mistake, but did you really notice it here? Did it bother you? Like everything in this piece, it's subtle, so it works.

When you see how a master composes a picture, the notion of having to choose one template can seem silly - when you can change or combine templates to suit your needs. There's no law stopping you. And then, people come up with arbitrary rules based on these templates, like you should never put your focal point in the middle? And yet, great artists do that all the time (see below!).

Another annoying fact is that so many of the templates overlap - what's the exact difference between an O and a C template? Or a tunnel? Can you really tell the difference in practice? What about an X versus a V or a Y template? Are they really that different? And did the great masters ever use any of this?

And another issue, most of these templates are concerned with achieving balance and harmony - all the different parts working together to create beauty. But, as I have explained in previous lessons, those aren't the only goals of composition. There are questions of clarity, legibility, mood and focus, whether you're trying to honestly portray your subject, idealize it, dramatize it, romanticize it, obscure it, or ridicule it:

There's a lot more to composition than pretty pictures.

How do I compose a picture?

My concern is how to pull people into my work so that they forget they're seeing a painting as they take in a scene and-or story. In my work, drawing and painting is like teleportation - I want to put you into the scene, and I use various tricks to do so. My favorite is to go off on a long walk, taking photos of everything, and choosing the photos that work best, with a great subject, a great patterning of shapes and colors, and with elements near and far and all around, to give you a strong sense of place. The resulting images probably resemble some compositional template (there are so many, it's hard not to), but the resemblance is unintentional and trivial compared to how it grabs you and sticks you into the scene. With my photos - I really was there, and I'm good enough with a camera I can capture that feeling, working on large enough canvases so that, when you observe my work, you have to look up and down, left and right, just like in real life. I will explain more on tricks to increase the illusion later.

The Templates

What are the templates? Well, I have compiled here all of Edgar Payne's examples, along with a few extras that have become popular since his time. Here they are:

The Rule of Thirds

The idea behind this one is if you place your focal point (the most interesting part of your subject or scene) at one of the four possible intersections, then you'll have a pleasing, balanced composition. People say you should never place the focal point in the middle because it makes the composition static - meaning there's no reason to move your eyes away from the middle. People say that, but I've seen great artworks with the focal point in the middle. It's one of those rules that masters break all the time.The Golden Mean (Fibonacci Spiral)

This is a design created by cutting a square in half, and then using a protractor to extend the length, making a rectangle with this specific proportion:

The proportion creates an irrational number similar to 𝞹. If you place your focal point along the vertical line on the right, it's supposed to guarantee a balanced composition. It's basically a glorified "L" composition (see below). Note, no one will notice you've used the golden mean, unless you keep dividing your picture into the spiral seen above. Also note, people on the internet love to place a Fibonacci spiral randomly on all sorts of things - having nothing to do with the original artists' designs or intent:

The golden mean is treated as a secret of the ancients, but there's little evidence anyone of note has ever used it in their art.

The 'O' (Circular)

I discussed one of these above - The Music Lesson by William Merritt Chase. Please note, Edgar Payne himself said you don't want to make the 'O' too obvious - and it's not in the two examples he drew above. They're more like ovals.

The 'C'

Honestly, is this any different from the 'O' composition? Sure, the right half doesn't feel as rounded, but your eyes still look up and down and back to the left, in a circular way...

The 'S'

Stapleton Kearns warns about this template - that having a curve of the 'S' bump up against the frame forces your eyes out of the picture plane. I think it's more of an issue in some artworks than others. It depends on what else is in there to grab your attention. It does help emphasize depth. Note, you can stack a couple S's on top of each other for a stronger effect.

The 'Z'

This is similar enough to an 'S' that hardly anyone talks about it, but I enjoy the sharper corners, especially if you stack a couple 'Z's on top of each other - it's great for overlapping shapes like waves or mountains:

The Big 'L'

As I wrote above, the L is perhaps the most overused of all the templates. I'll go one further and say the 'L' is basically the same as the cross scene below. The only difference is pushing the horizon line higher - big deal :D

The Cross, or Cruciform '+'

This is one of those templates you make by accident, whether you realize it or not, as soon as you add a tree, boat, or building that starts below the horizon and rises above it.

The 'X'

You might not see an 'X' when you look at this farmer, but the diagonal line of his farming tool contrasts with the lean of his torso. Usually, when people think of an 'X' template, they imagine a one-point perspective image, like this example by Andrew Loomis:

I will say, I've seen at least one painting by Leonardo Da Vinci that used one-point perspective in a creative fashion, although the result isn't an X, so much as a Radiating Lines composition - I suppose all 'X' compositions are actually just radiating lines. In this case, the energy of the angel Gabriel uses linear perspective to give a hidden radiating effect on Mary as she learns she will give birth to the Messiah.

Da Vinci also used radiating lines to make Jesus the main focal point of his last supper:

Note, Da Vinci placed Jesus' head exactly in the middle of the painting - a supposed big no-no in art composition... The next time a teacher complains, you can answer, "It was good enough for Da Vinci."

The 'Y'

I'm not sure how popular this template has been, apart from images of Jesus on the cross. Anyone else see an implied 'X' in here, or am I the only one?

The Triangle, or Pyramid

I think it's funny that the two examples by Payne look like they would better fit with the Silhouette template or the Three Spot. The most famous Triangular composition that I know of was this portrait of Mary, Jesus & John the Baptist, painted by Raffaello Sanzio:

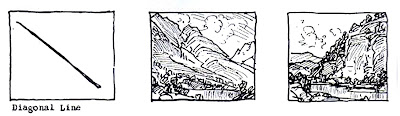

The Diagonal

I think it's fun to see how both of Payne's examples show a little counter diagonal line with the hills in the background - they're like 'X's where one line is stunted and small. Stapleton Kearns warned that, while these compositions can be nice, beginners often make the mistake of letting their trees lean at a diagonal, as if about to fall over. I go over all of Kearns's advice in this lesson here.

The Tunnel

Any path through the woods can give the impression of a tunnel, it's a good way to indicate depth - the path can curve left and write, in an S or C pattern, too. I made a tunnel composition recently for a teacher's art show:

I'm not sure how well the tunnel effect reads, but it's there. It's one of those things you can intuit, when you've taken enough photos.

The Silhouette

Note how triangular these examples are... Also note, they feel like a Group Mass...

The Pattern

This is another that I gravitate toward, I love complicated triangular shapes like leaves, that weave together and poke out at all angles. Payne warns not to let your patterns get too complicated. It's a fine line though, I find some complication to be quite dazzling:

Balanced Scales

I suppose the curving lines above should represent the arms of the scale? And yet, I see these examples as more of a Triangular shape. Ah well. Both Payne and Kearns warn about having two subjects on either side of equal weight and importance. Chase comes dangerously close to that in his Music Lesson above, but the girl's bright white dress brings her level of contrast up above that of the pianist.

The Fulcrum (See-Saw or Steel Yard)

These look like Big L's to me. Or are the Big L's a fulcrum? Looking back at the examples above, I suppose they are...

The Suspended Fulcrum (Steel Yard)

An L upside down.

Radiating Lines (the Spoke Wheel)

The 'X' composition revisited, this time with extra lines.

The 3 Spot

I assume, if one can get away with a 3 spot composition, you could make a 2 spot or 4 spot template as well. Even 5 or 6 spot - although you don't want to get too complicated. Also, how are these not Triangular compositions? Connect the dots and that's what you have in each of these...

The Group Mass (The Dog Pile)

These are just rotund cross compositions. Honestly...

Comments

Post a Comment