A bit of the history of China:

The history of China encompasses thousands of years, dating back to Neolithic tribes in 10,000 BC. Written history in China starts roughly around 2000 BC with the Xia Dynasty, not long after the development of ancient Egypt. Chinese and Egyptian cultures share some similarities, in so much as both formed and held continuous traditions, aesthetics, religion and philosophy that lasted thousands of years. Indeed, some argue that Chinese art represents the longest, unbroken tradition in the world.

This tradition is largely decorative. The emperors of China employed workshops and factories for centuries to make fine jewelry, textiles, porcelain, jade sculpture, carved lacquer, and other crafts. These items did more than serve the emperor in his home. They were given to surrounding lands as a display of wealth and power. Like with much of European history, most of the artisans who made these items were anonymous trades people, their names forgotten.

China also has a long, proud history of painting, particularly in calligraphy and ink wash painting, in which many master artists stand out. Landscapes were considered the highest form of painting. Portraits were specially made for ancestor veneration in family homes. Certain collectors (even emperors) periodically added stamps over these paintings to show ownership and, sometimes, to add a poem of their own:

Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains, by Wang Meng, 1366

Chinese architecture has also remained a constant aesthetic, with temples, palaces, and pagodas that vary only in decoration over the ages. These forms have had a major impact in shaping the architecture of the region, from Korea, Vietnam and Japan all the way to the west, where Chinese styles and decorations were referred to as Chinoiserie. Chinese palaces tend to be low and very wide, with great big roofs that seem to float over the structure.

Ancient China: the Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties (2070 - 256 BC)

Ancient China was the home for many different Neolithic tribes, most named after the places of archaeological sites. A famous one is at Liangzhu, where the following items were found:

Cong, from the Liangzhu Culture, 3300-2500 BC, AP Artwork.

Cong (detail), from the Liangzhu Culture, 3300-2500 BC, AP Artwork.

Bi, from the Liangzhu Culture, 3300-2500 BC, AP Artwork.

One of the oldest Chinese traditions was the belief in Feng shui, which was and still is a guiding force in Chinese aesthetics. It's based on the belief that ancestral ghosts and other mysterious forces and energies shape the world we live in. One can placate them by building shrines, and finding just the right spot, not just for burials, but for homes, shops, gardens, basically everything. This notion of finding the right spot sounds a lot like the way we compose a picture. But in this case, it's not just a question of balancing the picture, or telling a story. In Feng shui, it's putting your home and your life in alignment with everything: with your ancestors, with the stars above, with the lay of the land, and so on. It really is using aesthetics to create peace of mind and heart, through the belief, however unscientific, that in following Feng shui, you will have peace and prosperity, that you won't get sick or fall victim to some calamity. For millennia, people turned to Feng shui for safety - and in the meantime enjoyed the benefits of a beautiful, balanced design to everything around them. How could you argue with that?

Jade Figure, Xia Dynasty, 2000-1600 BC

Bronze Vessel, Shang Dynasty, 1400-1200 BC

Jade Figure, Shang Dynasty, 1200-1050 BC

Bronze Goblet, Shang Dynasty, 1150-1050 BC

Bronze Houmuwu Ding, Shang Dynasty, 1112 BC

Bronze Hu Vessel, Zhou Dynasty, 770-476 BC

In the 7th century, China began building border walls to protect it from foreign enemies.

Laozi was a legendary writer and philosopher from the 6th century BC, who founded the philosophy/religion of Taoism. He was so influential that emperors of the later Tang dynasty claimed him as their ancestor. Taosim, like Bhuddism, championed a simple, humble, and frugal way of life. It claimed everything in the world came from one source of energy - Tao. In Taoist religion, observants worshiped Laozi as a deity.

Confucius was a politician and philosopher of the Zhou Dynasty (550-479BC). He advocated a monotheistic religion in which man should strive to become one with God (Tian), by contemplating all of God's creation - in other words, by observing and making rational conclusions. And, when everyone does this, you get an ideal community. Confucianism and Taoism competed with each other for acceptance over the next several centuries.

The oldest temple dedicated to Confucius, built in 479 BC in his hometown of Qufu, the year after he died.

The building above was built with a central axis, facing north to south. The southern gate is named after a star, to signify Confucius as a star from heaven. The roof is made of yellow tiles, normally reserved for emperors. This temple has survived many fires and vandalism, and was largely rebuilt in the Ming dynasty, which is why so much of its decoration and styling resemble that of the Forbidden City (see below). The building and its many courtyards contain hundreds of stelae, or carved stones with inscriptions from various emperors and dynasties, some carved in the shape of tortoises.

Bronze & Silver Canteen, Zhou Dynasty, 300-200 BC

Pu Vessel with a Dragon, Zhou Dynasty

The Qin and Han Dynasties (221 BC - 220 AD)

Shi Huang (who reigned 220-206 BC) was founder of the Qin Dynasty, and the first emperor of a unified China. He expanded and connected several border walls, beginning what would eventually be the Great Wall of China.

The Terracotta Soldiers at Xi'an, 3rd Century BC

Confucianism was actually banned during the Qin dynasty, but proponents survived to pass it on to younger generations. In fact, the founder of the Han Dynasty, Emperor Han Gao Zu offered a sacrifice to the spirit of Confucius in his tomb (195 BC). Over the years, different emperors built temples to venerate Confucius, and during the Tang dynasty, it was decreed that all provinces and counties should have a Confucian temple, so they spread throughout China.

Red & Black Lacquerware Tray, Han Dynasty, 200-100 BC

A Painted Ceramic Vase, Han Dynasty, 206 BC - 8 AD

Artists in the Han dynasty developed the art of Gongbi, a careful, meticulous, systematic, highly detailed and realistic form of ink brush painting which used a variety of colors. While some Gongbi artists painted birds and flowers, some of the greatest used this style to paint courtly narrative stories of royalty. These were painted on large, horizontal hand scrolls - normally kept rolled up, and taken out for guests to admire. This style of painting was very popular and collectable among royal families, peaking in the Song dynasty, and continuing up to the end of the Ming dynasty. The opposite of Gongbi, called Hsieh Yi, was a loose, expressive way of free hand ink painting, meant to be more poetic than realistic.

The 3 Kingdoms, 6 Kingdoms, and North & South Dynasties (220 - 589)

Buddha Triad, Eastern Wei Dynasty, 500-600 BC

Ceramic Vase, Northern Qi Dynasty, 550-577

During the South Dynasty period the artist Zhang Sengyou (490-540) developed a form of painting called Mogu, or "boneless". It contained no preliminary drawing whatsoever, instead forming images entirely from ink and color washes.

Xie He (6th C.) was a painter, art historian, and critic who defined the six principles of painting:

1. "Spirit Resonance" or vitality

2. "Bone Method" referred to the brush strokes and how they related to the artist's unique personality.

3. "Correspondence to the subject" in other words, creating a likeness.

4. "Suitability to Type" referred to the application of proper colors, value, and tone.

5. "Division and Planning" i.e. composition

6. "Transmission by Copying" meaning both painting from life, and painting studies from the masters.

The Sui & Tang Dynasties (581 - 907)

The Zhouzhou Bridge, the oldest stone bridge still standing in China, built from 595-605

The Xumi Pagoda, Tang Dynasty, built in 636

The Giant Wild Goose Pagoda, in Chang'an, Tang Dynasty, built in 652

Tomb Guard (Wushi Yong), Tang Dynasty, 700-725

The Small Wild Goose Pagoda, Tang Dynasty, built in 709

The Giant Buddha of Leshan, Tang Dynasty, built from 713-803

Ceramic Dish, Tang Dynasty, 700-800

Ceramic Horse, Tang Dynasty

The Tang dynasty was very influential in Chinese history. This is when the philosophy of Zen (or Chan) Bhuddism arose, eventually spreading throughout eastern Asia. Zen advocated a life of simplicity, spontaneity, and self-expression.

During the Tang dynasty, a new form of ink wash painting became popular, using only black ink, and working less meticulously than the Gongbi form that was also popular at this time. With ink wash painting, capturing the spirit or essence of a subject was more important than direct likeness. It's almost like a Chinese version of Impressionism. It was painted mostly on hanging scrolls, by scholar-officials (the Literati class) who combined it with the art of poetry and calligraphy. They mainly painted works as gifts, knowing that a picture to the right person could help them gain a promotion among the intricate royal bureaucracy.

Imaginary landscapes were a particularly popular subject, developing into the Shan Shui genre, meaning "mountain water". There were three elements of Shan Shui painting: the path, the threshold, and the heart. The path might actually be a river or stream, but it's meandering path would lead the eye around the work, until coming to a threshold, or stopping point, usually a mountain. The heart of the artwork was its focal point. It could be anything, a person, an animal, but it was most important, as it defined the meaning of the work. Shan Shui was meant as a vehicle for philosophy, something to ponder, which is why it was often accompanied by a Shan Shui poem.

Strolling About in Spring, by Zhan Ziqian (Gongbi painter, c. 550-600)

detail from

Tribute Bearers, by Yan Liben and Yan Lide, painted somewhere between 600-673

Yan Liben (Gongbi painter, c. 600–673) of the Tang dynasty. He told his son, "I had studied well when I was young, and it was fortunate of me to have avoided being turned away from official service and to be known for my abilities. However, now I am only known for my painting skills, and I end up serving like a servant. This is shameful. Do not learn this skill."

Wang Wei (Southern School painter, 699-759) of the Tang dynasty. Wang was most famous as a poet, and over 400 of his poems survive. Although he was widely admired as a painter and musician, none of his works in these arts remain. He advocated the importance of the "Four Arts" that all scholar-officials should know: Qin Qi Shu Hua. These were the ability to play a musical instrument, paint, write calligraphy, and to play a strategy board game (Qi). These four skills soon became expected for all people of this class. It's ironic that none of these arts were as important to these scholars as their ability as statesmen and politicians. Yet today, we care most about their art, not their political careers.

Zhang Xuan (Gongbi painter, 713–755)

Zhou Fang (Gongbi painter, c. 730–800)

Zhang Zou (8th C, Tang Dynasty) used innovative techniques, like painting ink wash directly with his fingers, not just a brush.

The 10 Kingdoms Period, Liao, Song, Western Xia, Jin, and Yuan Dynasties (907 - 1368)

A Bird-and-Flower painting by Huang Quan, somewhere between 920-960

During the 10 Kingdoms Period, two artists, Huang Quan (903-965) and Xu Xi (died before 975) founded the Mogu genre of Huaniaohua (bird-and-flower paintings). Both this and the Gongbi style of painting reached their peak popularity during the Song dynasty, which is considered the "Great Age of Chinese Landscape Painting". This was also the time when Jing Hao and his student Guan Tong developed the Northern School, a style of monumental landscape painting.

Later in the Song dynasty, Xia Gui and Ma Yuan formed the Ma-Xia School, known for its simplified, striking landscape compositions.

At the beginning of the Yuan Dynasty, Marco Polo (1254-1324) of Italy, journeyed east to discover and write about China, India, Persia, Mongolia, Japan, and other eastern countries, starting new trade routes and cultural interaction with Europe.

Toward the end of the Yuan Dynasty Bhuddist monks from China traveled to Japan, where they brought the tradition of ink wash painting, including Huaniaohua.

Jing Hao (Northern School, 855-915)

Guan Tong (Northern School, 906-960)

Luxuriant Forest among Distant Peaks, by Li Cheng (Northern Song School, 919-967) Don Yuan (Southern School, c. 934-62)

Gu Hongzhong (Gongbi painter, 937–975)

Travelers Among Mountains and Streams, by Fan Kuan (Northern Song School, c. 960-1030)

Cizhou Taibozun Celadon, Song Dynasty, made between 1000-1200

Celadon is an iron oxide glaze with a range of color similar to jade, from light or olive green to blue, brown and cream color. This made it very popular for ceramics.

Sgraffito Vase, Song Dynasty, between 1000-1200

Yaozhou Ware Celadon with Peony Scrolls, Song Dynasty, between 1000-1200

Early Spring, by

Guo Xi (Ink Brush painter, c.1020 – c. 1090 AD) Su Shi (poet & essayist, 1037-1101)

1045 Lingxiao Pagoda, in Zhengding, Hebei Province, Song Dynasty, built in 1045

Detail from Duke Wen of Jin Recovering His State, attributed to Li Tang (Northern School, 1050-1130) who was known for his "axe-cut brush-strokes". Mi Fu (Southern School, 1051-1107)

Li Jei (architect, 1065-1110) who wrote the Yingzao Fashi, an influential book on architectural standards and practices, which emperor Huizong had published and distributed. It's one of the greatest books on Chinese architecture and construction, and Li Jei became the Director of Palace Buildings. It's very practical, focusing on standard units of measurement, the proper way to join wooden beams, the forumulas for mixing paints and glazes, and many other directions. While it's not the first comprehensive book on Chinese architecture, it is the oldest text that has survived to the present in its entirety.

The main hall of the Longxing Temple in Zhengding, Hebei Province, built in 1052

The Pagoda of Fogong Temple in Shanxi, built in 1056

Jade Cup, Song Dynasty, 1100-1300

Jian Tea Bowl, Song Dynasty, 1100-1200

In Ceramics, Jian ware, named after the city Jianyang, were simple stoneware vessels with subtle glazes that exemplified Buddhist aesthetics, and were also highly prized in Japan, where it was called Tenmoku. A similar style, Jizhou was mostly black, and often had leaves or paper cut outs placed inside to create resist patterns:

Jizhou tea bowl with leave pattern inside, 100-1279

These vessels were preferred for tea ceremonies, not only for style, but their ability to retain heat. Jian ware and Jizhou ware reached their peak perfection in the Song dynasty.

Liang Kai (Northern School, c. 1140-1210) known as Madman Liang

Ma Yuan (Northern School, 1160-1225)

Chengling Pagoda, south of Zhengding, Hebei Province, Song Dynasty, built in 1161-1189

Detail from Pure and Remote View of Streams and Mountains by Xia Gui (Northern School, 1195-1224) considered one of the greatest of all Chinese painters

Longquan celadon ware, Zhejiang, Song Dynasty, between 1200-1300

Muqi (1210?-1269?) While not much is known about this master, he is considered the greatest Zen bhuddist painter of all time.

Early Autumn, by Qian Xuan (Shan Shui & Bird & Flower painter, 1235-1305) Gao Kegong (Ink Brush painter, 1248–1310)

Stone Cliff at the Pond of Heaven, by Huang Gongwang (Southern School, 1269-1354), 1341

Jade Ornament, Yuan Dynasty, made between 1271-1368

Wu Zhen (Southern School, 1280-1354)

Yan Hui (active 1280-1300)

Portrait of Kublai Khan, founder of the Yuan Dynasty, by Araniko (1245-1306), 1294

Jar with Fish and Water Plants, Yuan Dynasty, 1300-1400

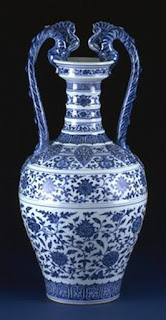

Vase with Dragon and Peony Scrolls, Yuan Dynasty, 1300-1400

Plate with Baoxiang-hua Scrolls, Yuan Dynasty, 1300-1400

Plate with Chrysanthemums & Peony, Yuan Dynasty, 1300-1400

Vase, Yuan Dynasty, 1300-1400

Ni Zan (Southern School, 1301-1374)

Fang Congyi (Southern School, 1302-1393)

Wang Meng (Southern School, 1308-1385)

Bailin Temple Pagoda, Zhaoxian County, Hebei Province, built in 1330

The Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368 - 1911)

The most famous parts of the Great Wall of China were built during the Ming Dynasty:

Jar, early Ming Dynasty, made between 1350-1400

Porcelain Plate, Peony Design, Hongwu Period, made between 1368-1398

Employing Virtue, by

Dai Jin (ink brush painter, 1388-1462) who founded the Zhe School of painting - a conservative style that referred back to the Ma-Xa school.

The Sakyamuni Buddha, Ming Dynasty, made between1400-1500

Carved Lacquer Box, made between 1403-1424

The Temple of Heaven, Ming Dynasty, built from 1406-1420

The Forbidden City, in the Imperial City of Beijing, built from 1406-1420

The Forbidden City (Zijin Cheng) was the home of China's emperors for over 500 years, from the Ming to the end of the Qing dynasty. It consists of over 980 buildings, Which comprise the largest collection of ancient, preserved wooden structures in the world. It is surrounded by a wall almost 8m tall, and a moat, and then by many large parks and temples of the Imperial City. While huge, there are actually several other Chinese palaces that exceed it in size. The city was designed as a physical manifestation of the imperial code of ethics.

The name, "Forbidden City" is actually a mistranslation. In Chinese, Zi refers to the north star, as the emperor was considered celestial. Zijin refers to the celestial emperor's home on Earth, and the Jin part was mistranslated as meaning forbidden. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, it was called Da Nei, or Palace City. The palace is now referred to as Gùgōng, or former palace.

This walled city had four gates, north, south, east, and west. The southern gate goes out to Tiananmen Square. A central road called the Imperial Way goes straight through these north and south gates, and continues all the way to Jingshan in the north and The Gate of China (now destroyed) in the south. Only the emperor could travel on this road.

The city contains many huge meeting halls, palaces, and temples. It conformed to ideas of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, with temples for each of these religions. The Emperor and his wife each had their own palace, Yin and Yang, and another in the middle where they could meet, "creating harmony." As yellow was the color emblematic of the emperor, only the emperor's royal buildings were allowed to use yellow roof tiles. The only buildings with other colors are the black roof of the library, symbolizing water and thus, fire prevention, and then the green tiles of the princes' palaces, representing growth.

Poetic Feeling of Falling Flowers, by

Shen Zhou (ink brush painter 1427-1509) who founded the Wu School of painting, a group of amateur painter scholars who would write inscriptions explaining the method and reason for their painting.

Watching the Spring and Listening to the Wind, by

Tang Yin (Gongbi painter, 1470–1524) Wen Zhengming (ink brush painter, 1470-1559)

Chen Chun (bird-and-flower painter, 1483-1544)

Portrait of Confucius, by

Qiu Ying (Gongbi painter, 1494–1552)

Bamboo, by

Xu Wei (ink brush painter, 1521-1593) Was also a poet and playwright.

Bottle with Baoxiang-hua Scrolls, Jiajing Period, made between 1522-66

Kinrande Bottle, Jiajing Period, made between 1522-66

Vase, Ming Period, made between 1522-66

Zacai Jar with a Dragon, Jiajing Period, made between 1522-66

Dong Qichang (ink brush painter, 1555-1636)

Plate with a Peony Design, Wanli Period, Ming Dynasty, made between 1573-1620

Plate with a Taoist Immortal Design, Wanli Period, Ming Dynasty, made between 1573-1620

Wang Shimin (ink brush painter, 1592-1680)

Wang Jian (ink brush painter, 1598-1677)

Gosu-Akae Plate, Ming Dynasty, made between 1600-1700

Two Birds, by

Bada Shanren (ink brush painter, 1626-1705) - an innovative painter, he was a major influence for the Shanghai school that came later.

A Thousand Miles Along the Jangtse, by

Wang Hui (ink brush painter, 1632-1717) Spring Comes to the Lake,

Wu Li (ink brush painter, 1632-1718) who converted to Catholicism.

Searching for Immortals, by

Shitao (ink brush painter, 1642-1707)Wang Yuanqi (ink brush painter, 1642-1715)

Jade Ornament, Qing Dynasty, made somewhere between 1644-1911

Porcelain Jar, Qing Dynasty, made between 1662-1722

Porcelain Jar, Qing Dynasty, made between 1662-1722

Porcelain Vase, Qing Dynasty, made between 1662-1722

Huang Shen (ink brush painter, 1682-1772) one of the 8 eccentrics

Porcelain Vase, Qing Dynasty, made between 1690-1700

Porcelain Pilgrim Flask, Qing Dynasty, 1700-1800

Porcelain Vase, Qing Period, 1723-35

Porcelain Lantern, Qing Dynasty, 1725-50

Jade Incense Burner, Qing Dynasty, 1736-95

Vase, Qing Dynasty, 1736-95

Ox Vessel, Qing Dynasty, 1736-95

Snuff Bottle, Qing Dynasty, 1796-1820

Snuff Bottle, Qing Dynasty, 1813-1861

Ren Xiong (Shanghai School painter, 1823-1857)

Xu Gu (ink brush painter, 1824-1896)

The late Qing period was a time of instability. China lost the First Opium War (1839-42) to Great Britain, which opened up several ports to foreign trade. Then, there was the Taiping Rebellion (1850-64) between the Qing dynasty and Han China.

A Scene from the Taiping Rebellion

Shanghai became a melting pot of foreigners, leading to a new style of painting known as the Shanghai School. This school formed the first major break from traditional Literati painting, breaking with conventions and the deep symbolism of previous generations. Shanghai school painters focused on the visual content of their work. They exaggerated forms and brightened colors in bold new ways.

Pu Hua (Shanghai School painter, 1834-1911)

Ron Bonian (Shanghai School painter, 1840-1896)

Qi Baishi (Shanghai School painter, 1864-1957)

Wang Zhen (Yiting) (Shanghai School painter, 1867-1938)

Modern China (1911 - The Present)

The philosophy of China as it related to art:

How was Chinese culture represented in other arts – music, architecture, and literature?

What made it great?

Some leading figures:

.jpg)

%20w%20Leaf.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment