7. Art of Medieval Europe (The Middle/Dark Ages) (400AD – 1500AD)

A bit of historical context:

It’s challenging to try to briefly describe 1100 years of human history and how it relates to the evolution of art––there is simply too much information––nations that rose and fell, wars and invasions, kings and queens, cathedrals and abbeys, and so on. You don’t have to know all of it, but you should know a few key facts, including how it started, what it developed into, and, most fascinating to me, what medieval life was like, because it was so different from today.

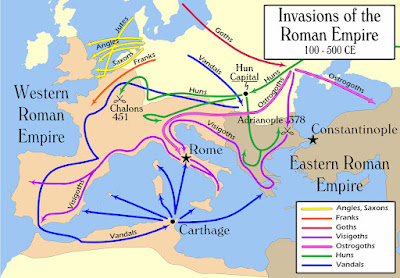

The Middle Ages began with the fall and sacking of Rome in the west, the ruin of its cities, foreign invasions, and population decline. The last Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, gave up the throne in 476, but his empire had already been weakened by centuries of civil war and rivalry. The power vacuum this created led to centuries of chaos and war as rival factions roamed the continent, fighting for land. As these fledgling nations settled and established themselves, they began to develop anew so that by around AD 1000, Europe began to transform into a stronger, more advanced society. Advances in farming (the horse collar, horse shoes, and the heavy plow), and using Byzantium as a buffer against invading Turks, led to the population of Europe booming from only 18 million in 650 to over 70 million by 1347. This was when the Black Plague struck, killing up to a third of the population in just three years.

Several developments changed European society:

Monasticism: starting with St. Anthony of Egypt in the 2nd century, Christian monasteries became suppositories of knowledge, teaching monks to read and write, to preserve ancient texts, and to craft devotional art. In 529, Benedict of Nursia created the Benedictine Order, with rules limiting and governing the behavior of all monks, including abbotts. This order discouraged laziness––Benedict wrote, “Idleness is the enemy of the soul.”

The Roman Catholic Church Under The Pope: became a major power under the leadership of Pope Gregory the Great (590-604). The church used its influence to limit the power of kings and worked to bring Christian leaders together. This would have major consequences during The Crusades.

Islamic Math & Science: al-Khwarizmi (c. 780-850) wrote The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing, which was translated into Latin and introduced Europe to algebra and equations.

It’s worth considering some questions that scholars still debate today, including:

Did the rise of Christianity really hold back human progress?

While it’s true that the chaos of the Middle Ages made it hard to advance, what with all the wars and suffering it caused, but advances did eventually come. And it’s true the population did decline following the fall of Rome – and you need a dense population in order to support people who specialize in fields other than food production. But you can hardly blame Christianity for that when it was the “pagan” forces of the north doing the pillaging. Nor can you blame Christianity for Rome’s weakness; that had more to do with weak leadership – centuries of it, where, too often, power-sharing schemes led to civil wars, and powerful generals simply seized power.

Having said that, there were instances of the church interfering with scientific and cultural progress, not only at this time, but also during the Renaissance and beyond (see Lesson 7 on the High Renaissance to learn of the Spanish Inquisition). Conflict between religion and science is still ongoing today on a variety of topics, and during medieval times the church had no qualms about punishing people for heresy, iconoclasm, and even witchcraft. Notions of justice were also primitive – with trial by combat still permissible (in England) until 1819.

There are also other factors at play in the woes of the dark ages. According to historian Michael McCormick, there was a volcanic eruption (possibly two) in 536 AD so powerful it plunged the world into a year long winter, causing world-wide famine and plague, and plunging Europe into a century of economic collapse.

Were the Dark Ages really so dark?

The people living there didn’t think so. They referred to the birth of Christianity as the modern or “new” era, as Petrarch called it - and we still refer to the Bible in terms of "old" and "new" testaments. They also believed, at various points, that they were living in the end times. People usually think of medieval times as dark because of the rise of feudalism, serfdom, and the general lack of opportunities or modern medicine. And all this is certainly true. Yet, it's worth noting, the medieval period was one of growth and increasing wealth that allowed for the rise of mercantilism, a new middle class, and the flowering of the Renaissance. The Renaissance didn't just happen by itself, it was the result of hundreds of years of struggle and development.

What was life like for everyday people back then?

This is a great question... stay tuned for an update.

What about the art? What was it like?

While one might assume art at this time was dedicated solely to God and the church, it wasn’t. Artists made a number of secular crafts, especially as Europeans gained more and more wealth. Unfortunately, much of it has been lost to time. During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, medieval artefacts were considered unfashionable and embarrassing – many were discarded or melted down. Palaces and other buildings were destroyed and rebuilt in more modern styles. So, what little is left comes mostly from the church, or from archaeological excavation.

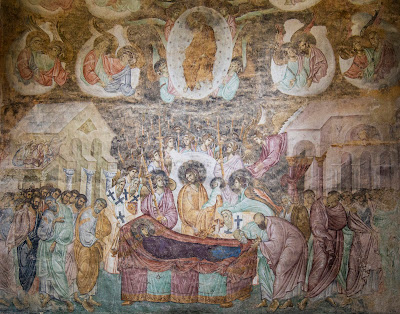

The medieval art we typically study (that survived) consists mainly of churches and the devotional arts used to decorate them: altars, sculptures, mosaics, frescoes, stained-glass windows, tapestries, illuminated Bibles and other books, embroidery, and metalwork, like crosses, plates, chalices, reliquaries, candlesticks, censers, and so on. While Christian, many pagan ideas and symbols found their way into these artworks.

With such a length of time, there are different ways to break up this age in history. Some have simplified it into early, high, and late periods. Art historians have made it a bit more complex, with seven overlapping periods, based on changing tastes and innovations of the time. The overlap comes from some places holding to traditions longer than others, and there are lots of regional differences. Viking art, in particular, is very distinctive. It all goes to show how messy history can be, with few clear dividing lines:

Migration Period: 375-568

Merovingian Period: 400-800 (in France)

Insular Period: 600-1000 (Britain & Ireland)

Carolingian: 790-900

Ottonian: 900-1000

Romanesque: 1000-1200

Gothic: 1100-1500 (extending well into the Renaissance)

The Migration Period (375-568)

This refers to a time when roving Germanic tribes travelled and pillaged their way around the ancient world, eventually settling down.

These migrations led to the settlement of Europe as we know it today, and the development of Romance languages such as Italian, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and Romanian.

(French) Merovingian Period: 400-800

Art at this time shifted away from sculpture, limited to simple decorations on sarcophagi and altars, instead focusing on the new art of book making – illuminated manuscripts. These works integrated pagan animal-style decoration with Greco-Roman designs. The Merovingian line of French kings built churches and monasteries at this time – some from wood, some from stone, but few survive intact today. Most were rebuilt. Church designers mostly continued the basilica plan used in classical Rome.

Insular Period: 600-1000 (Britain & Ireland)

Merovingian craftsmen travelled to Britain where they brought the arts of glassmaking, and illuminated manuscripts. This period also marks the time when Vikings began raiding Europe, from the 8th to 11th centuries, the Hungarians in the 9th and 10th centuries, and the Saracens (in Persia) at various times.

This is one of two identical clasps, meant to hold a leather cuirass together at the shoulders. They were found on the site of Sutton Hoo - a farm land with several hills close together, that appeared man-made. The owner hired an amateur archeologist to examine them, and they discovered an ancient burial ship, filled with treasure! This was the traditional way to bury kings in olden times, in this case most likely King Rædwald of East Anglia. The news quickly traveled, and soon a team of professional archeologists took control of the site. They discovered 18 burial mounds in one of the most important archeological finds of all time. And it was just someone's back yard!

The clasps shown above feature enamel, garnet stones, and two common metalworking techniques. The interlacing snakes along the borders have been chip-cut, while the raised lines on the sides are filigree. This is an ancient technique of placing small gold wire or balls on top of the surface, and soldering it together in complex patterns.

Although abstract and hard to see, this clasp features animals, common to jewelry of this time – the two sides feature boar’s heads. The belt buckle below has a diagram to help show how many animals can fit in a typical item of jewelry:

The Carolingian Age (790-900)

This was named for Charlemagne (Charles the Great), who united Europe through 50 military campaigns, spreading Christianity in the process. For this, the Pope named him the first Holy Roman Emperor. In addition, Charlemagne promoted education with the preservation of ancient texts and the introduction of a new standard for writing and punctuation, called Carolingian miniscule. Although Charlemagne’s empire fell, its contributions endured. From the Carolingian Period onwards, Europe experienced an explosion of wealth and success.

Wealth was necessary for the cathedrals and other arts they created. One abbey, upon deciding to create three Bibles, calculated it would require 1,600 calves to make all the necessary parchment. Another expensive material was lapis lazuli, a blue stone imported from Afghanistan, made to make Ultramarine pigment. Other expensive materials included imported wood and ivory.

Carolingian churches copied the idea of the Roman Basilica, but added westwork, meaning a decorative entrance on the west side of the church – usually with two towers and several floors of balconies between them. This was the predecessor of later Gothic facades.

The Ottonian Period (900-1000)

This comes from the three Holy Roman Emperors named Otto. These emperors wanted to re-establish ties to early Christendom, so they promoted late Roman, Byzantine, and Carolingian art forms. The best works of this time are the illuminated manuscripts, sponsored directly by the emperors. This period marked the beginning of a global warming that benefited agriculture, further helping increase populations, lasting up to the Gothic period.

Romanesque: 1000-1200

This period of art is mostly known for its architectural style, which began in France, and was the first to spread throughout Europe. It consisted mostly of constructing larger cathedrals, with massive walls, vaulted ceilings, and round-headed arches and windows.

Last Judgment Detail with the Gluttonous Man Tortured, Church of Sainte‐Foy, Conques, France, an AP Art Image.

Major Historical Events of the Romanesque Period:

At this time the Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches split (1054). 1095 Also marked the start of the Holy Wars.

The Romanesque Period was also when Normandy successfully invaded England, in 1066, an event immortalized by the Bayeux Tapestry:

Gothic Art 1100AD – 1500AD

Major Historical Events of the Gothic Period:

Marco Polo travelled west into China from 1271-1295.

1347 began the Black Death – the plague which wiped out a third of Europe by 1350.

1453, Constantinople fell and became Istanbul, Turkey.

1492 Christopher Columbus sailed his first of many voyages across the Atlantic to the New World.

1517 The Protestant Reformation split the Catholic church, beginning hundreds of years of warfare throughout Europe.

Some leading figures:

Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274)

Petrarch (Italian, 1304-1374)

How was it represented in the other arts – music, architecture, and literature?

Life and culture at this time was centered on the Christian church. Churches were built and decorated. Services were held daily. People devoted a great deal of time to writing music for church, particularly Gregorian chant. And, monks and other scribes recorded copies of the Bible and other religious texts.

What made it great?

The quality, and the intricacy of the patterns. It’s rare to find such a work of genius put into such a simple thing as a brooch to hold your tunic together. It’s fun to be able to hold something so close and see its intricacy, and then step back and see a larger, simpler design.

%20Looped%20Fibulae%20AP.jpg)

,%20Bayeux%20Tapestry%20AP.webp)

,%20Palazzo%20Vecchio%20AP.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment